Corpus Delicti

The Latin term corpus delicti refers to the principle that there must be some proof that a crime has been committed before a person can be convicted of having committed that crime. In Western law, the term has also been widely used to refer to the object upon which the crime was committed, meaning a body, in the case of a murder, which itself proves the crime was committed. To explore this concept, consider the following corpus delicti definition.

Definition of Corpus Delicti

- noun. A fundamental fact required to prove that a particular crime was committed.

- noun. The material substance or object upon which a crime has been committed.

Origin 1825-1835 New Latin (“body of the offense”)

What is Corpus Delicti

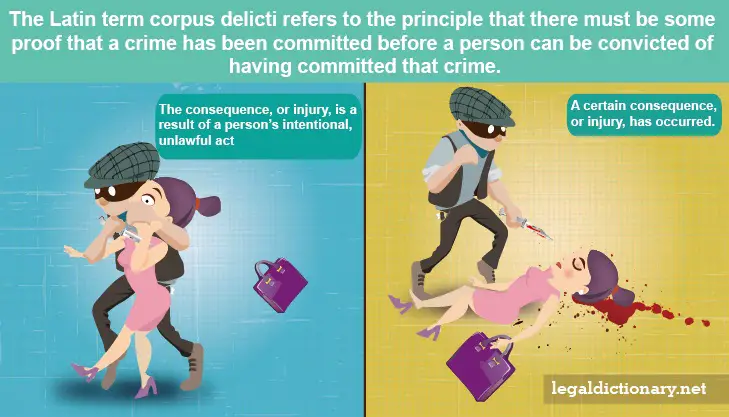

The term corpus delicti, which literally means “body of crime,” is best understood in realizing a person cannot be put on trial for a crime, unless it is first proven that the crime happened to begin with. In other words, the prosecution would need to demonstrate that something bad happened as a result of a law having been violated, and that someone – the defendant – was the one who violated it. There are two elements of corpus delicti in any offense:

- A certain consequence, or injury, has occurred

- The consequence, or injury, is a result of a person’s intentional, unlawful act

For example:

Steven believes that his neighbor, Frank, stole his lawnmower from his backyard. He makes a police report, but acknowledges that he has no proof that Frank took it, but claims that Frank has coveted the lawnmower, and he must have taken it because it is missing. In order for the district attorney’s office to be able to prosecute Frank for the crime of theft, there must be proof that (1) Steven’s lawnmower was stolen, and (2) that Frank stole it.

Statements by other neighbors seem to support Frank’s claim that Steven has memory lapses, and that he frequently accuses neighbors and other people of wrongdoing. In this example, corpus delicti has not been proven, as there is no evidence a crime has actually been committed, neither is there evidence that any person is criminally responsible for anything.

Corpus Delicti and a Confession

When someone confesses to a crime, the issue of corpus delicti becomes a little more tricky, as a person’s confession, without substantial proof that the required elements of corpus delicti exist, is not generally sufficient to convict the person. As a matter of fact, a person’s statement, or confession, may not even be admissible in court, if the prosecution has not already presented some independent evidence that that the crime even occurred.

For example:

Thomas appears at the police station and confesses to having killed Beth, but nobody has reported that Beth is missing, and there is no body. Thomas cannot be charged with murder – what if Beth turned up a couple of weeks later, alive and well? If Beth doesn’t come home, however, and an investigation ensues, but no body is found, and there is no actual evidence that something untoward happened to her, the prosecution is likely to have a more difficult time demonstrating the corpus delicti, as there is no body of evidence.

In this example of corpus delicti, this speaks not only to the fact that there is no body, but no evidence, other than Beth’s absence, which might be explained any number of ways, that a crime was even committed.

The purpose of this rule is to reduce the risk of convicting someone based solely on his confession, for a crime that didn’t even happen. The rule also helps to reduce the use of interrogation tactics that tend to strong-arm confessions, and to encourage the use of painstaking investigations.

The Issue of ‘No Corpse, No Crime’

Throughout the years, television and big screen crime dramas have portrayed corpus delicti in the sense that, if there is no body, there is no crime. In other words, Hollywood’s interpretation has been that a defendant cannot be convicted of murder if a corpse cannot be produced. This is not true. While the principle of corpus delicti guides the integrity of the investigation and prosecution process, modern investigation techniques and evidence interpretation are often enough to gain a conviction in the absence of a body.

Remember that the Latin term means “the body of the offense,” not necessarily referring to the body of the victim. To convict someone of murder in such a case, the prosecution must first prove the two required elements, that the victim was killed, and that the death was the result of a criminal act, using evidence other than what might be found on the missing body. In this way, the legal system defines corpus delicti as the fact of a crime having actually been committed.

Example of Corpus Delicti in Arson Cases

While the term corpus delicti commonly makes people to think of the need for a body in a murder case, it is necessary to have this “body of evidence” in other types of crime as well. Arson cases are especially challenging to prosecute, as the state must show proof that (1) a fire occurred, causing damages, and (2) the fire was caused by a criminal or intentional act, rather than accident or nature. Arson cases require the same presentation of evidence surrounding the fact of the crime, other than a person’s confession, as murder.

For example:

Leanne put her two small children to bed, then when out to the apartment complex laundry room for a few minutes, leaving a couple of scented candles lit on the table. The cat knocked the candles off the table, where they caught a stack of papers on the floor on fire. Leanne had gotten distracted by a neighbor, staying to chat for a bit while the girls slept. Suddenly, Leanne heard screaming and, when she headed back to her apartment, she realized it was engulfed in flames.

Leanne choked and sputtered from smoke inhalation as she tried to run inside to get her kids, but the fire had already spread too far. While the neighbor held Leanne outside, a firefighter went in and brought the girls out, but one of them died quickly of smoke inhalation, and the other was terribly burned. Being suspicious of the fact that Leanne wasn’t in the apartment with her children when the fire started, police question her. In her grief, Leanne confesses “I started the fire – I killed my baby!”

The investigation turns up no evidence that the fire was started intentionally, but an eager prosecutor takes Leanne to trial based on her confession. In the same way a confession is not enough to convict a person of murder, it cannot be the sole basis of convicting someone of criminal arson. In this example of corpus delicti, the fire in Leanne’s apartment was started by accident, and is therefore not a crime, but a horrible tragedy nonetheless.

Corpus Delicti Example in Woman’s Disappearance

On a warm August night in 1985, Carolyn Kenyon left her apartment, headed for her boyfriend’s house in shorts and her bare feet. She told her roommate she would be home by midnight, and didn’t take anything with her, not even her ID or her medications. Carolyn was never seen or heard from again. Dozens of people helped search for Carolyn, but her disappearance remained a mystery.

Five years later, the boyfriend, James McMahan, was being questioned in connection with the murder of a 10-year old little girl. He gave three separate statements to police in Detroit, confessing to killing the girl, as well as to killing his wife, Cheryl, and Carolyn Kenyon. As police attempted to gain more information about Carolyn, McMahan said the two of them were drinking and smoking marijuana at his house, when she made him angry, and he stabbed her in the chest.

McMahan told investigators that he had first buried Carolyn in his basement, then moved her body to another location, before finally placing it in trash bags, and into a city dumpster. Police followed all of these leads in an attempt to find Carolyn’s body, or any other evidence of the crime, in an attempt to satisfy corpus delicti, but were unsuccessful. McMahan was charged and tried for Carolyn’s murder, based on his confession. The confession was allowed to be read during trial, and the jury convicted him of second degree murder.

McMahan appealed the conviction, based on the fact that there simply was no evidence other than the confession police had recorded. The appellate court reversed the conviction, stating:

“While we believe that the evidence presented establishes the death of Carolyn Kenyon, the evidence is almost nonexistent to show some criminal agency as the cause of death independently of defendant’s confession.”

The case was not finished there, however, as the prosecution appealed the reversal to the Michigan Supreme Court. The Supreme Court confirmed the appellate court’s decision to reverse the conviction, holding that the fundamental purpose of the corpus delicti rule is to “guard against, indeed to preclude, conviction for a criminal homicide when none was committed,” and to “minimize the weight of a confession and require collateral evidence to support a conviction.”

The Court went on to explain that the corpus delicti of a murder requires not only proof that a death occurred, but that it was caused by some criminal act. All of this must be proven by some evidence other than the defendant’s confession. Once such circumstantial evidence has been provided, the confession of the accused may be properly introduced at trial.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Confession – A formal statement admitting that one is guilty of having committed a crime.

- Evidence – The body of facts and information indicating whether a proposition, belief, or circumstance is true.