Eminent Domain

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forbids the taking of private property for public use without “just compensation.” The authority of Federal, state, and local governments to take private property for public use, providing just compensation to the owner, is called “eminent domain.” Real estate, or land, is not the only property subject to eminent domain law, but water and air rights as well. To explore this concept, consider the following eminent domain definition.

Definition of Eminent Domain

Noun

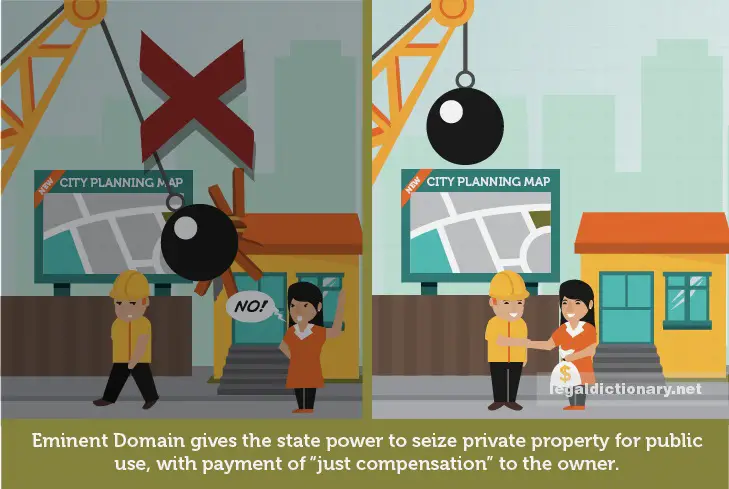

- The power of the state, by virtue of its sovereign power over the lands within its jurisdiction, to seize private property for public use, with payment of “just compensation” to the owner(s).

Origin

1625 Discussed in the legal discourse “De Jure Belli et Pacis,” by Dutch professor of law Hugo Grotius, as dominium eminens (Latin: supreme lordship)

History of Eminent Domain Law

The notion of eminent domain has existed since ancient times, as documented in the Bible when Samaria’s King Ahab offered compensation to Naboth for his vineyard. Early European nobility commonly took what land they wanted, until 1789, when France publicly recognized the rights of property owners to be compensated for such property seizures.

The practice of eminent domain came to the American colonies as commonly held British law. While drafting the Constitution, conflicting ideas about this practice surfaced, a compromise of which resulted in the final clause to the Fifth Amendment, specifying that compensation was to be made for property seized for public use.

In modern times, eminent domain law is widely used by federal and state governments, and has been upheld by the Supreme Court. Eminent domain law facilitates the creation and upkeep of such necessary infrastructure as roads and highways, parks, and public buildings, as well as water, power, and gas lines. Additionally, eminent domain may be used for urban renewal, replacement of deteriorated housing with new low-cost housing, and beautification of public use areas.

A 1954 Supreme Court decision in Berman v. Parker upheld that it is within the government’s power to use eminent domain to ensure the community is not only healthy, clean, and well patrolled, but that it is beautiful, spacious, and well balanced. In other words, that the term “public use” could properly be construed as that which is in the public’s interest, or for the public’s welfare.

To further the effectiveness of the eminent domain power, the Supreme Court decided, in the 2005 case of Kelo v. City of New London, that the transferring of land from one private owner to another private owner for the purpose of economic development is a permissible definition of “public use.”

Eminent Domain Pros and Cons

Eminent domain has been a topic of disparate opinions since before it was set down in writing in the Constitution. Indeed, there are both pros and cons to the practice. For example, eminent domain was used in the 1950s redevelopment of an impoverished neighborhood in San Francisco. While the ramshackle homes were replaced with cosmopolitan hotels and other modern edifices, more than 4,000 poverty-stricken denizens, and over 700 businesses were evicted, the buildings demolished and removed.

While it is usually clear that the use of eminent domain to build roads, improve utilities, and revitalize cities, many property owners fear they will not be compensated fully for the seizure of their land. Additionally, as these projects are often paid for with tax dollars, many taxpayers feel that the requirement of paying for land acquired through eminent domain places a monetary burden too great for the perceived benefit of the project.

Eminent Domain Examples

Eminent domain has indeed been used to the benefit of the community in which it has been exercised, but examples of over-reaching or poor planning abound, sparking further controversy. Below are several highly publicized examples of eminent domain cases.

Kelo v. City of New London

The plan to raze the Fort Trumbull district of New London, Connecticut sparked the 2005 Supreme Court ruling that more broadly defined the scope of eminent domain. The plan was for the revitalization of the neighborhood to attract large companies to the area, bringing with them much-needed jobs. Indeed, Pfizer Pharmaceutical expanded to New London, and an upscale hotel, athletic center, conference center, and office park were planned to further update the area. Unfortunately, the massive pharmaceutical company packed up and left town a mere five years after the ruling, taking with it its more than 1,000 jobs. The 70-acre stretch of land on the Thames River that is Fort Trumbull remains mostly empty, the plan for more than 100 rental condominiums to take the place of the previously planned buildings has been held up in a contract dispute ever since.

Julia Lemon v. Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital

In 2005, the state of Georgia, on behalf of Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital, attempted to seize a property for the building of a daycare center to serve Georgia’s largest hospital. On the property stood a home owned by Julie Montgomery, and rented by 93-year old Julia Lemon. The hospital offered owner Montgomery the “fair market value” of the property at about $50,000, but she was loathe to displace her elderly tenant, who had lived there for 26 years. The Dougherty County Super Court issued a 2006 ruling on the matter requiring the hospital to pay Montgomery $200,000 for her property, as well as paying $51,000 to Lemon to aid in her relocation. This case emphasizes that the use of eminent domain cannot be all-reaching, but should examine real-life issues when considering property seizures.

Bauder v. Delaware County

Scott and Kathy Bauder fought Delaware County Ohio’s eminent domain grab at the land they had farmed for a quarter of a century, declining the county’s offer of a mere $450,000 for a 10-acre stretch of land that split their holdings. The land was to be used to extend Sawmill Parkway into the Delaware city limits, but the Bauder’s attorneys argued that the area already has adequate roadways.

The jury in the 2013 hearing found that the land was worth a great deal more than the county had offered the Bauders, though not the $1.2 million suggested by a privately employed appraiser. In the end, the county was ordered to pay $850,000 for the land, and an additional $100,000 to cover the Bauder’s legal fees. This decision is typical in such cases, where juries often split the difference between the estimated land values.

The Eminent Domain Appraisal and Fair Market Value

When appropriating property through eminent domain, the government must pay the owner “fair market value” for the property. Fair market value is generally considered to be the amount a buyer and seller are likely agree to if that property was sold on a particular day. For example, the highest amount the seller and a buyer might reasonably agree to on a particular day is considered fair.

Determining fair market value requires an eminent domain appraisal, which is a valuation more than one real estate appraiser. Competent real estate appraisers experienced in eminent domain valuation are often hired by the parties’ eminent domain attorneys. Real estate appraisers often have experience specific to particular home styles and regions, making it important to hire an appraiser experienced in eminent domain cases in the area in which the property lies.

What is Eminent Domain Compensation

Property owners often have questions about eminent domain compensation in cases where only part of a property is seized, as well as whether payment is made for improvements to, or businesses on, the property or businesses, as well as who is entitled to eminent domain compensation in cases where the property has a tenant.

Compensation for Improvements

The law entitles property owners to compensation for improvements made to the property in addition to its land value. Such improvements may include buildings, fencing, paved roads, and even machinery. In many jurisdictions, valuation of improvements is to take into consideration the particular improvement as it relates to the property’s ongoing value, rather than salvage value or replacement cost.

Compensation for Business Losses

In most states, property owners are not entitled to compensation for business losses as a result of the property being seized in eminent domain actions. California, however, allows for compensation for loss of business “goodwill,” or the value of the sustainable income that results from the business’s location, reputation, and other issues that ensure continued patronage.

Compensation for Partial Property Seizure

In many eminent domain cases, only a portion of the property is taken, such as the strip of land needed to widen a street. In these instances, the entire property is not seized, but compensation is made for the actual part taken, as well as for the damage to the remaining property. Such damages, called “severance damages,” may occur when the strip of land taken, such as for a roadway or utility easement, splits a larger property, or when the portion taken somehow diminishes the value or usefulness of the remaining property. Severance damages may also be necessary to cover damages to a property caused by the actual construction project for which properties were seized.

Compensation for Rented Property

In the event a property seized under eminent domain is rented or leased, it may be required that both the property owner and the tenant be compensated. The valuation of compensation for rented property in such a case may differ depending on whether the lease or rental agreement contained a condemnation clause. In some eminent domain cases, such a tenant may be entitled to receive a significant portion of eminent domain compensation made for the property.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Condemnation Clause. A clause specifying what would occur if the leased property was taken by eminent domain. An effective condemnation clause should define partial and total condemnation, whether the lease agreement may be terminated, and by which party, and who is entitled to compensation for damages.

- Replacement Cost. The amount required to replace an asset at its condition prior to the loss. Replacement cost often differs from the item’s market value, and does not deduct an amount for depreciation.

- Salvage Value. The estimated value of a property, improvement, or other asset at the end of its useful life. Subtracting an asset’s salvage value from its cost provides the amount to be depreciated.