Judicial Review

In the United States, the courts have the ability to scrutinize statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions to determine whether they violate provisions of existing laws, or whether they violate the individual State or United States Constitution. A court having judicial review power, such as the United States Supreme Court, may choose to quash or invalidate statutes, laws, and decisions that conflict with a higher authority. Judicial review is a part of the checks and balances system in which the judiciary branch of the government supervises the legislative and executive branches of the government. To explore this concept, consider the following judicial review definition.

Definition of Judicial Review

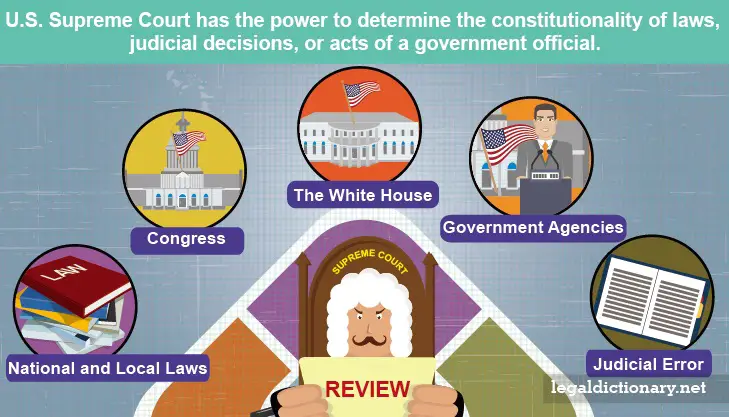

- Noun. The power of the U.S. Supreme Court to determine the constitutionality of laws, judicial decisions, or acts of a government official.

Origin: Early 1800s U.S. Supreme Court

What is Judicial Review

While the authors of the U.S. Constitution were unsure whether the federal courts should have the power to review and overturn executive and congressional acts, the Supreme Court itself established its power of judicial review in the early 1800s with the case of Marbury v. Madison (5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 2L Ed. 60). The case arose out of the political wrangling that occurred in the weeks before President John Adams left office for Thomas Jefferson.

The new President and Congress overturned the many judiciary appointments Adams had made at the end of his term, and overturned the Congressional act that had increased the number of Presidential judicial appointments. For the first time in the history of the new republic, the Supreme Court ruled that an act of Congress was unconstitutional. By asserting that it is emphatically the judicial branch’s province to state and clarify what the law actually is, the court assured its position and power over judicial review.

Topics Subject to Judicial Review

The judicial review process exists to help ensure no law enacted, or action taken, by the other branches of government, or by lower courts, contradicts the U.S. Constitution. In this, the U.S. Supreme Court is the “supreme law of the land.” Individual State Supreme Courts have the power of judicial review over state laws and actions, charged with making rulings consistent with their state constitutions. Topics that may be brought before the Supreme Court may include:

- Executive actions or orders made by the President

- Regulations issued by a government agency

- Legislative actions or laws made by Congress

- State and local laws

- Judicial error

Judicial Review Example Cases

Throughout the years, the Supreme Court has made many important decisions on issues of civil rights, rights of persons accused of crimes, censorship, freedom of religion, and other basic human rights. Below are some notable examples.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

The history of modern day Miranda rights begins in 1963, when Ernesto Miranda was arrested for, and interrogated about, the rape of an 18-year-old woman in Phoenix, Arizona. During the lengthy interrogation, Miranda, who had never requested a lawyer, confessed and was later convicted of rape and sent to prison. Later, an attorney appealed the case, requesting judicial review by the Supreme Court, claiming that Ernesto Miranda’s rights had been violated, as he never knew he didn’t have to speak at all with the police.

The Supreme Court, in 1966, overturned Miranda’s conviction, and the court ruled that all suspects must be informed of their right to an attorney, as well as their right to say nothing, before questioning by law enforcement. The ruling declared that any statement, confession, or evidence obtained prior to informing the person of their rights would not be admissible in court. While Miranda was retried and ultimately convicted again, this landmark Supreme Court ruling resulted in the commonly heard “Miranda Rights” read to suspects by police everywhere in the country.

Weeks v. United States (1914)

Federal agents, suspecting Fremont Weeks was distributing illegal lottery chances through the U.S. mail system, entered and searched his home, taking some of his personal papers with them. The agents later returned to Weeks’ house to collect more evidence, taking with them letters and envelopes from his drawers. Although the agents had no search warrant, seized items were used to convict Weeks of operating an illegal gambling ring.

The matter was brought to judicial review before the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether Weeks’ Fourth Amendment right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure, as well as his Fifth Amendment right to not testify against himself, had been violated. The Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled that the agents had unlawfully searched for, seized, and kept Weeks’ letters. This landmark ruling led to the “Exclusionary Rule,” which prohibits the use of evidence obtained in an illegal search in trial.

Plessey v. Ferguson (1869)

Having been arrested and convicted for violating the law requiring “Blacks” to ride in separate train cars, Homer Plessey appealed to the Supreme Court, stating the so called “Jim Crow” laws violated his 14th Amendment right to receive “equal protection under the law.” During the judicial review, the state argued that Plessey and other Blacks were receiving equal treatment, but separately. The Court upheld Plessey’s conviction, and ruled that the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to “equal facilities,” not the “same facilities.” In this ruling, the Supreme Court created the principle of “separate but equal.”

United States v. Nixon (“Watergate”) (1974)

During the 1972 election campaign between Republican President Richard Nixon and Democratic Senator George McGovern, the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate building was burglarized. Special federal prosecutor Archibald Cox was assigned to investigate the matter, but Nixon had him fired before he could complete the investigation. The new prosecutor obtained a subpoena ordering Nixon to release certain documents and tape recordings that almost certainly contained evidence against the President.

Nixon, asserting an “absolute executive privilege” regarding any communications between high government officials and those who assist and advise them, produced heavily edited transcripts of 43 taped conversations, asking in the same instant that the subpoena be quashed and the transcripts disregarded. The Supreme Court first ruled that the prosecutor had submitted sufficient evidence to obtain the subpoena, then specifically addressed the issue of executive privilege. Nixon’s declaration of an “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” was flatly rejected. In the midst of this “Watergate scandal,” Nixon resigned from office just 15 days later, on August 9, 1974.

The Authority Behind Judicial Review

Interestingly, Article III of the U.S. Constitution does not specifically give the judicial branch the authority of judicial review. It states specifically:

“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.”

This language clearly does not state whether the Supreme Court has the power to reverse acts of Congress. The power of judicial review has been garnered by assumption of that power:

- Power From the People. Alexander Hamilton, rather than attempting to prove that the Supreme Court had the power of judicial review, simply assumed it did. He then focused his efforts on persuading the people that the power of judicial review was a positive thing for the people of the land.

- Constitution Binding on Congress. Hamilton referred to the section that states “No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid,” and pointed out that judicial review would be needed to oversee acts of Congress that may violate the Constitution.

- The Supreme Court’s Charge to Interpret the Law. Hamilton observed that the Constitution must be seen as a fundamental law, specifically stated to be the supreme law of the land. As the courts have the distinct responsibility of interpreting the law, the power of judicial review belongs with the Supreme Court.

What Cases are Eligible for Judicial Review

Although one party or another is going to be unhappy with a judgment or verdict in most court cases, not every case is eligible for appeal. In fact, there must be some legal grounds for an appeal, primarily a reversible error in the trial procedures, or the violation of Constitutional rights. Examples of reversible error include:

- Jurisdiction. The court wrongly assumes jurisdiction in a case over which another court has exclusive jurisdiction.

- Admission or Exclusion of Evidence. The court incorrectly applies rules or laws to either admit or deny the admission of certain vital evidence in the case. If such evidence proves to be a key element in the outcome of the trial, the judgment may be reversed on appeal.

- Jury Instructions. If, in giving the jury instructions on how to apply the law to a specific case, the judge has applied the wrong law, or an inaccurate interpretation of the correct law, and that error is found to have been prejudicial to the outcome of the case, the verdict may be overturned on judicial review.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Executive Privilege – The principle that the President of the United States has the right to withhold information from Congress, the courts, and the public, if it jeopardizes national security, or because disclosure of such information would be detrimental to the best interests of the Executive Branch.

- Jim Crow Laws – The legal practice of racial segregation in many states from the 1880s through the 1960s. Named after a popular black character in minstrel shows, the Jim Crow laws imposed punishments for such things as keeping company with members of another race, interracial marriage, and failure of business owners to keep white and black patrons separated.

- Judicial Decision – A decision made by a judge regarding the matter or case at hand.

- Overturn – To change a decision or judgment so that it becomes the opposite of what it was originally.

- Search Warrant – A court order that authorizes law enforcement officers or agents to search a person or a place for the purpose of obtaining evidence or contraband for use in criminal prosecution.