Exclusionary Rule

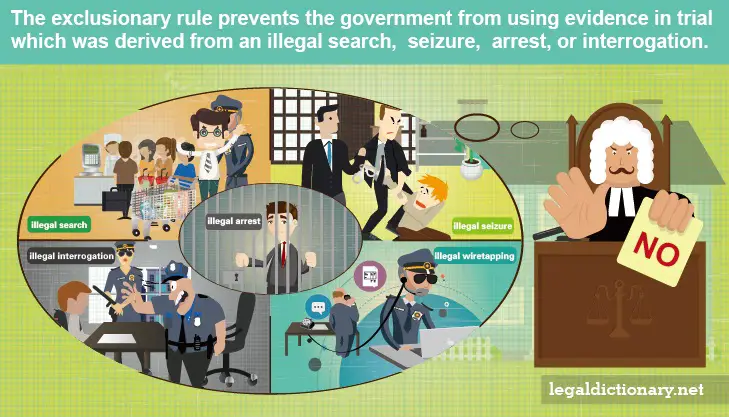

The exclusionary rule prevents the government from presenting evidence in trial which was gathered in violation of the Fourth Amendment’s protection against illegal search and seizure. A doctrine commonly used in American courts, the exclusionary rule discourages police and other law enforcement agents from obtaining evidence illegally. The court will suppress or ban evidence that was gathered in violation of the defendant’s Fourth Amendment right to be protected against unlawful search and seizure.

If evidence is suppressed, it means that the evidence cannot be shown or discussed during the defendant’s trial. This rule applies to any evidence that is the direct product of a constitutional violation. To explore this concept, consider the following exclusionary rule definition.

Definition of Exclusionary Rule

Noun. Any rule that allows for the exclusion or suppression of evidence.

Origin 1375-1425 late Middle English

Fourth Amendment Rights

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects citizens “against unreasonable searches and seizures.” It further states that no warrants shall be issued without probable cause, which means that the privacy of citizens may not be violated without compelling reasons to do so.

Fruit of the Poisonous Tree

The legal doctrine known as “fruit of the poisonous tree” states that evidence derived from an illegal search, seizure, arrest, or interrogation is not admissible in a court of law because the evidence was tainted by fact that the method used to obtain the evidence was illegal. For example, police put a wiretap on a suspected drug dealer’s phone and began listening to and recording conversations without first obtaining a warrant. The suspect reveals that he has drugs stashed away under a dumpster where the buyer could pick them up. The police find the dumpster and seize the drugs before the buyer arrives. The illegally recorded phone calls would not be admissible (the poisonous tree), nor would the drugs found as a result of the illegal wiretap (the fruit).

Exceptions to the Exclusionary Rule

There are many exceptions to the exclusionary rule, which primarily serves to protect the constitutional rights of the accused, though not to the extent that justice cannot be served. Below are the primary exceptions to the exclusionary rule:

- Good Faith Exception. An exception allowing evidence obtained by law enforcement or police officers who rely on a search warrant they believe to be valid to be admitted at trial.

- Attenuation Doctrine. An exception permitting evidence improperly obtained to be admitted at trial if the connection between the evidence and the illegal means by which it was obtained is very remote.

- Independent Source Doctrine. An exception permitting evidence obtained illegally to be admitted at trial if the evidence was later obtained by an independent person through legal activities.

- Inevitable Discovery Rule. An exception permitting improperly obtained evidence to be admitted when it is apparent that the evidence would have eventually been discovered through legal means.

Motion to Suppress Evidence

A motion to suppress evidence is a request that the court exclude certain evidence from the trial proceedings. The defense may argue that the evidence was illegally obtained, or that the evidence is not relevant to the matter at hand. A motion to suppress evidence is typically made before the trial begins. Motions to suppress evidence are often made in Fourth Amendment search and seizure cases where evidence may have been obtained during a search for which there was no warrant. If the motion is granted, and that particular evidence was critical to the prosecution’s case, the case may be dismissed.

Exclusionary Rule Cases

Courts deal with the issue of evidence gathering each and every day. As a result of the debate over which evidence should or should not be allowed at trial, a number of landmark Supreme Court decisions have been made.

Arizona v. Gant 556 U.S. 332

This exclusionary rule case was an important Supreme Court decision, as it deals with both the exclusionary rule and the good faith exception when it comes to law enforcement officers searching vehicles subsequent to arrest.

Arizona police arrested Rodney Gant for driving with a suspended license. After handcuffing him and placing him in a squad car, the officer conducted a search of Gant’s vehicle, finding a gun and a bag of cocaine. Gant’s attorney filed a motion to suppress the gun and drugs from being used as evidence because they were obtained without a warrant, in violation of Gant’s Fourth Amendment protection against illegal search and seizure. Gant’s motion was denied the court which ruled that the gun and cocaine were found during a legitimate traffic stop, and therefore, Gant’s Fourth Amendment rights were not violated.

Gant appealed the decision to the Arizona Court of Appeals, which reversed the lower court’s decision on the grounds that the warrantless search of the vehicle was, indeed, unconstitutional. The Arizona Supreme Court agreed with the Court of Appeals, leading to a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court by Arizona’s Attorney General. The issue brought to the Supreme Court is whether searches and seizures that the police perform after handcuffing a defendant and securing a crime scene is in violation of an individual’s Fourth Amendment protection to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

The Supreme Court ruled that Gant’s Fourth Amendment rights had been violated by the warrantless search of his vehicle. The Court’s reasoning was that, since the suspect and the crime scene had been secured, the police needed to obtain a warrant before conducting a search of the contents of Gant’s vehicle.

United States v. Jones 132 S.Ct. 945 (2012)

Antoine Jones, owner of a nightclub in the District of Columbia, was suspected of drug trafficking, and a great deal of information was gathered in the police investigation. Based on evidence already gathered by police, they were able to obtain a warrant to place a GPS tracking device on a Jeep registered to Jones’s wife, of which Jones was the primary driver. The police were given 10 days to install the device on Jones’s vehicle, and it was required to be installed in the District of Columbia. The police, however, did not install the device until 11 days later, at which time the vehicle was in Maryland. The police proceeded to use the device to track the vehicle for the next 28 days, during which time the device relayed over 2000 pages of data.

Antoine Jones was indicted on conspiracy to distribute, and possession with intent to distribute cocaine and cocaine base. Before trial, Jones’s attorney filed a motion to suppress the evidence gained from the GPS device, arguing that the evidence was gathered in violation of his Fourth Amendment right against unlawful search and seizure. The District Court granted the motion to suppress part of the evidence. The suppressed evidence included data gathered while the Jeep was parked in the garage at the Jones residence, as people have a reasonable expectation of privacy while at home, while on public roads, no such principle applies.

The question raised by this case is whether the attachment of a GPS device to a vehicle and the use of that vehicle on public streets constitute a search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment and whether a defendant has a reasonable expectation of privacy while driving on public roads. The court held that the government’s installation of the GPS tracking device does constitute a search. The warrant was not valid in that the conditions of its issuance, relative to the time and location of installation, were not met. As such, the GPS surveillance constituted an unlawful search and the exclusionary rule was applied to all the evidence and data gathered as a result of the GPS device.

Arizona v. Evans 514 U.S. 1 (1995)

In 1990, Isaac Evans was stopped by a Phoenix police officer for driving the wrong way down a one-way street. Evans informed the officer that his license had been suspended, and a subsequent warrant check confirmed that the license was suspended, and informed the officer of an outstanding warrant. The officer placed Evans under arrest and searched his car, discovered a bag of marijuana, adding a charge of possession to Evans’ arrest. It turned out that the warrant had been quashed by the court more than two weeks prior to the arrest, and that a clerical error failed to remove it from the system.

Evans’ attorney moved to suppress the marijuana as it was the “fruit of an unlawful arrest.” The trial court granted the motion to suppress, but the decision was reversed when the Arizona Court of Appeals ruled that the purpose of the exclusionary rule was not intended to deter clerical staff, and justice would not be served by excluding evidence in the case.

The matter was brought to the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether evidence obtained with a warrant, due to a clerical error, is deemed invalid, and is subject to the exclusionary rule. The Supreme Court reversed the Appellate court ruling, holding that the rule does not apply when an error is made by non-law enforcement personnel or clerical staff. In this case, the arresting officer acted on good faith, having a reasonable belief that the computer’s results were valid.

Related Terms and Issues

- Warrant A writ issued by a judge directing a law enforcement officer to conduct a search, seizure, or make an arrest.

- Probable Cause The minimum amount of evidence required before a search, seizure or arrest can be properly made.